Comincio con un ricordo, che rivivo come la scena di un film. Giovanni e Francesca Falcone sono seduti con altri amici intorno al tavolo da pranzo di casa nostra. Si fanno discorsi più o meno seri con l’intermezzo degli immancabili giochi di parole…

Risalgo alla data: era giovedì 14 maggio 1992 ed era l’ultima volta in cui ci saremmo visti, ma nessuno poteva immaginarlo e la serata passò in allegria, come altre prima, sostenuta dallo scoppiettare delle sue battute ironiche. La stessa ironia con cui mi aveva ripetuto più volte che a Roma poteva muoversi con relativa libertà, ma in Sicilia era soltanto “un morto che cammina”. E la profezia si avverò nel modo che tutti ricordiamo, quel sabato 23 maggio 1992.

Per giorni e settimane, la strage riempì pagine di giornali e palinsesti di radio e televisioni, praticamente in tutto il mondo. Ma in Italia la risposta della cosiddetta gente fu diversa. C’era un silenzio che restituiva il senso di un dolore vero, sentito; di una lacerazione che ora univa un intero Paese contro quella barbarie.

A colpirmi, in particolare, era stata la reazione tanto composta quanto corale dei palermitani. In pochi giorni, finestre e balconi si erano riempiti di lenzuola bianche: un’espressione inedita e un messaggio forte, muto come il lutto.

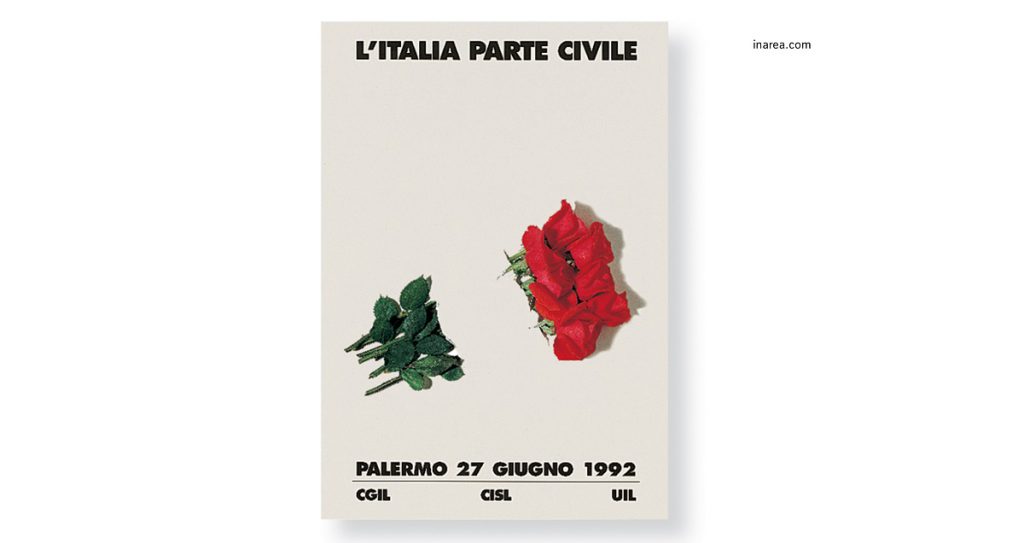

Quando CGIL, CISL e UIL proclamarono la prima manifestazione nazionale a Palermo, mi fu chiesto di pensare a un manifesto, un messaggio in grado di dare voce allo sdegno di un intero popolo. Davanti al foglio bianco, la reazione istintiva fu l’associazione con quelle lenzuola, ma doveva esserci anche un’icona, un simbolo capace di arrivare al cuore di chi guarda.

Lacerai il foglio proprio al centro con due strappi che correvano paralleli e feci passare all’interno delle rose rosse spezzate. L’effetto mi colpì e mi commosse. Anche uno sguardo distratto poteva “leggere” i messaggi impliciti: i fiori deposti sulla tomba, il senso delle rose e delle vite recise e, ancora, la singolare ricomposizione della bandiera italiana.

Legai la composizione a un titolo che a sua volta poteva essere letto almeno in due accezioni diverse: “L’ITALIA PARTE CIVILE”. Nel 2000, l’Associazione Nazionale Magistrati adottò quell’immagine come icona simbolo per ricordare tutti i giudici uccisi dalla mafia e dal terrorismo.

Quando però mi capita di rivedere “le rose spezzate”, il ricordo torna a quei momenti dolorosi. Dolore che, dal 25 febbraio scorso, si è acuito perché è uscita di scena un’altra figura straordinaria, legata a quella stagione, Liliana Ferraro, collega e collaboratrice di Giovanni Falcone. Così, per riequilibrare lo stato d’animo, corro con la memoria a ritrovare una bella serata della primavera di trent’anni fa, in cui eravamo tutti insieme. Giovedì 14 maggio 1992.

Thirty years on

I’d like to share a memory which I relive over and over again, like the scene in a film. Giovanni and Francesca Falcone are sitting around the dining table at our home: we are chatting about serious things and less-serious things too, laced with a flurry of witticisms…

It was Thursday, 14 May 1992: none of us could have imagined this was going to be the last time we would ever see each other again and the evening was merry, with the cracking of quips. The same bittersweet irony with which he kept telling me that he could move around fairly freely in Rome, whereas in Sicily he was “a dead man walking”. And the prophecy came true in the way we all remember, on that fateful Saturday, 23 May 1992.

For weeks, the massacre filled papers and TV and radio news reports practically all over the world. But in Italy, the response of the people was different: there was a dead silence that conveyed the sense of an aching wound, one that was uniting an entire country against that act of savagery.

I was particularly struck by the composure and community reaction of the people of Palermo. Within days, they began to hang white sheets from their windows and balconies: a strong message of silent mourning.

When the CGIL, CISL and UIL trade unions announced their first national demonstration in Palermo, I was asked to devise a poster that could give voice to the sense of outrage which was being felt by an entire nation.

With a blank sheet of paper in front of me, my instinctive reaction was to associate it with those white bed sheets, but I also needed to feature an iconic symbol that could touch the hearts of the beholders.

I made two tears at the centre and inserted a bunch of red roses in-between. The effect it achieved struck and moved me. Even the most absent-minded person would be able to “read” the implicit messages: flowers on a tomb, the analogy between cut roses and severed lives, as well as the extraordinary way in which this image ultimately comes together as the Italian flag.

I entitled the image “ITALY, THE CIVIL PARTY”, a phrase which in Italian has at least two different meanings. ln 2000, the Italian National Association of Magistrates adopted this image as an iconic emblem to honour all those judges who have been killed in the war against Mafia and terrorism.

And yet, whenever I happen to come across “the severed roses” image, I am reminded of those painful times. The pain has since become even more acute because on 25 February we have lost another exceptional person associated with that period: Liliana Ferraro, a colleague and collaborator of Giovanni Falcone. Therefore, in order to balance the sorrow, I delve inside my memory and go back to a beautiful spring evening in Rome thirty years ago when we were all together. Thursday, 14 May 1992.